Federalism on the Edge: Khaatumo’s Rise, Villa Somalia’s Reach, and the Stakes for Somalia’s Future

EDITORIAL | At first glance, the sudden declaration of the SSC-Khaatumo administration in Laascaanood may appear to be another local struggle in Somalia’s long and fractious history. But that would be a mistake — and a dangerous one. What’s happening in northern Somalia is not simply about borders or tribal affiliation. It’s a test of the very idea of federalism in Somalia, and whether it can survive a federal government that increasingly appears unwilling to respect the structures on which the post-conflict Somali state was built.

This week, Puntland — Somalia’s oldest and arguably most stable federal member state — issued a sharply worded statement rejecting the legitimacy of SSC-Khaatumo. It wasn’t a mild rebuke. It was a direct rejection of a political project viewed as illegal and destabilizing. According to Puntland, there has been no legal, inclusive, or constitutional process by which SSC-Khaatumo could declare autonomy from Puntland — and until such a process occurs, Sool and Cayn remain part of the Puntland state.

“Until a general consultation conference is held… Sool and Cayn remain part of Puntland,” the statement reads.

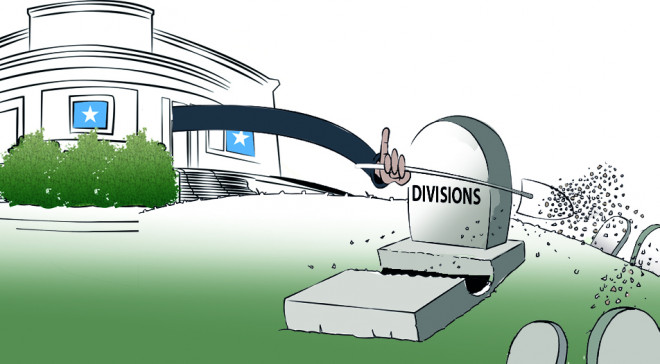

But what makes this statement truly remarkable isn’t just the language — it’s the warning embedded in it. Puntland doesn’t just see SSC-Khaatumo as a separatist project. It sees it as a symptom of something more corrosive: the deliberate undermining of federalism by Villa Somalia, the seat of federal power in Mogadishu. And in the context of a state still recovering from decades of collapse, that is a grave accusation.

To understand why this moment matters, it helps to revisit how Somalia’s federal experiment began. The fall of the central government in 1991 was more than a political breakdown. It was a social disintegration, a rupture so deep that warlords, clan militias, and — eventually — Islamist courts filled the vacuum. Amid this fragmentation, some regions, desperate for order, turned to federalism. It wasn’t imposed. It was chosen — built from the ground up by communities trying to reclaim agency in the face of chaos.

Puntland was the first to formalize this vision, declaring itself a federal member state in 1998. It wasn’t a bid for independence. It was a bet on the future of Somalia — a belief that the country could reassemble itself through cooperation and mutual respect. That founding included six regions: Bari, Nugal, Mudug (north), Sool, Sanaag, and Cayn.

Now, Villa Somalia appears to be rewriting the rules of that federal compact, bypassing the elders, sidestepping consultation, and attempting to fold Sanaag and Haylaan into the SSC-Khaatumo project — despite the loud and repeated objections of community leaders in those regions.

What’s worse is that this isn’t an isolated case. There’s a pattern emerging.

When the president of Jubaland held elections in accordance with constitutional timelines — and refused to support an illegal term extension proposed by Mogadishu — the federal government responded not with dialogue but with force. Troops were sent to Ras Kambooni, apparently with the aim of reshaping Jubaland’s leadership. The operation failed. But the implications were chilling. In Villa Somalia’s model of federalism, local autonomy only matters when it serves central interests.

That model isn’t just undemocratic. It’s dangerous. Just this week, Ethiopia’s National Intelligence and Security Service (NISS) announced the arrest of 82 suspected ISIS operatives across its major cities. These individuals were reportedly linked to ISIS in Puntland, where they had been trained before being deployed across Ethiopia in what appears to be a well-coordinated regional terror plot.

This alone should be a wake-up call. Ungoverned spaces — particularly those created or exploited by political manipulation — don’t just destabilize Somalia. They export insecurity.

Meanwhile, back in Laascaanood, another kind of battle is playing out. SSC-Khaatumo claims to represent the will of the people. Somaliland, invoking colonial-era borders, claims that Sool and Cayn fall under its authority. But the people of these regions — especially the elders and armed youth who expelled Somaliland forces — have said otherwise. Their allegiance, politically and culturally, remains with Puntland. They see SSC-Khaatumo not as a vehicle for self-determination but as a proxy of Mogadishu’s overreach.

Villa Somalia could have played a constructive role here — as a neutral convener, a protector of constitutional order. Instead, it has acted as a partisan actor. Rather than stabilize the federation, it is injecting volatility into it.

And that brings us back to Puntland’s stance. This isn’t about drawing lines on a map. It’s about defending a principle. The 1998 social contract that birthed Puntland was rooted in consultation and consensus. Any effort to alter it without the same process is not only illegitimate — it’s an affront to the very idea of federalism.

If Villa Somalia continues to redraw Somalia’s political map through backdoor channels, the consequences will be felt far beyond Puntland. What began as a promise of decentralized, inclusive governance is fast becoming a centralized order that resembles the very dictatorship Somalis once rejected.

Somalia deserves better. It deserves a federal system that lives up to its promise — one that reflects not just the text of a constitution but the spirit of its people.

Federalism in Somalia wasn’t granted from above. It was carved out from below — by negotiation, by sacrifice, and by faith in a shared future. If Villa Somalia still believes in that future, it must listen — really listen — to the voices coming from the periphery.

©Garowe Online Editorial Team Editorial Analysis | July 2025