Somalia’s Foreign Policy: Chaos, Self-Interest, or Lack of Vision?

Mogadishu—Since President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud took office in May 2022, Somalia’s foreign policy has faced challenges that underscore a lack of coherence and strategic vision. The Federal Government, eager to strengthen international relations, has instead embarked on a series of contradictory steps, creating confusion within the region and exposing an immaturity in the country’s diplomatic leadership.

A political rift emerged almost immediately. The memorandum of understanding between Somaliland and Ethiopia pushed Somalia into a direct confrontation with Ethiopia. This was no calculated diplomatic maneuver; it was a blunt political strike. There was no acknowledgment of Ethiopia’s strategic importance—a country that shares an expansive border with Somalia and has military forces stationed within its borders. Instead of employing long-term strategy, Somalia rushed to align itself militarily with Egypt, a move that exacerbated tensions and appeared to position Somalia as a direct adversary to Ethiopia.

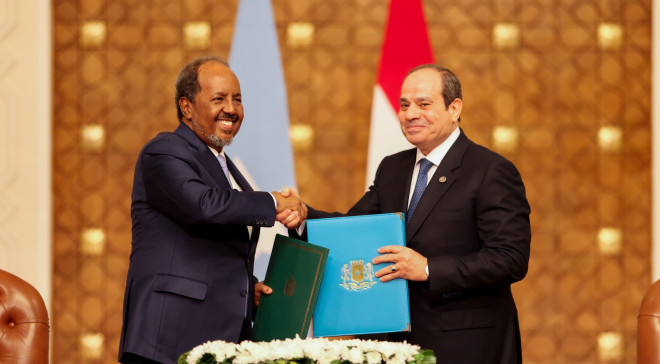

The trilateral agreement signed in Asmara by President Hassan Sheikh, Egyptian President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi, and Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki only deepened the perception of an anti-Ethiopia coalition. The move heightened regional anxieties, leaving many to wonder whether Somalia’s actions were truly aligned with its national interests.

Egypt, a country with historical ties to Somalia, has its own agenda. Long absent from the region’s political forefront during Somalia’s decades of instability, Egypt’s interests are tied to its simmering conflict with Ethiopia over the Nile River. Yet Somalia’s abrupt embrace of Egyptian military ties lacked foresight. What was Somalia trying to achieve? To many observers, it appeared the Federal Government was prioritizing external alliances over the careful, diplomatic navigation of its domestic and regional challenges.

As the regional tensions intensified, Turkey entered the picture. A key ally to Somalia in military and economic terms, Turkey applied pressure on President Hassan Sheikh to strike an agreement with Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed. This deal allowed Ethiopia to secure a place in post-ATMIS peacekeeping plans and granted Ethiopia unprecedented maritime access—an agreement that contradicted years of public assurances from Somali leadership to its citizens.

Inside Somalia, the deal provoked outrage. It was seen not just as a betrayal but as an outright reversal of the strategic vision Somalia had previously presented. The maritime concession undercut the alliance with Egypt and Eritrea, forcing Somalia to send delegations to Cairo and Asmara to explain its shift. The spectacle of these diplomatic back-and-forths exposed the fractured nature of Somalia’s foreign policy.

Turkey, with its far-reaching strategic interests, had already complicated matters. Its role as a close ally of both Somalia and Ethiopia added a layer of tension, particularly given Ankara’s strained relations with Cairo since the ousting of Egypt’s Mohamed Morsi. These overlapping rivalries spilled into Somalia’s regional posture, further entangling the country in the geopolitical web.

The diplomatic disarray escalated further following the Ankara agreement. Somalia dispatched a delegation led by the State Minister for Foreign Affairs to Addis Ababa, even as its own Ministry of Foreign Affairs issued a statement accusing Ethiopian forces of killing Somali soldiers in the border town of Doolow. Ethiopia promptly denied the accusations, sparking yet another public diplomatic embarrassment.

Such contradictory decisions highlight the Federal Government’s failure to craft a clear and consistent approach to foreign relations. Somalia seems torn between appeasing Egypt and Eritrea to maintain their alliance while simultaneously entering into deals that advance Ethiopia’s regional ambitions. The absence of a coherent strategy has underscored the immaturity of Somalia’s diplomatic leadership, leaving the nation vulnerable to further instability.

Public concern has grown. Many Somalis question the government’s decision-making processes, viewing them as reactive rather than strategic. The country’s geopolitical position remains underutilized, with its leadership failing to weigh the long-term implications of its foreign policy choices.

The blame, some argue, lies with a leadership circle dominated by President Hassan Sheikh and his allies. Allegations of personal interests driving policy decisions have only deepened the public’s distrust. Analysts and experts warn that Somalia must prioritize the development of a unified foreign policy centered on national interests.

Somalia cannot afford to become a battleground for regional powers. It must rise above its current predicament with a transparent and pragmatic diplomatic approach. The stakes are high, and only a measured foreign policy can deliver the stability and future prosperity that Somalia desperately needs.

GAROWE ONLINE