Somalia: Puntland Bristles as Somalia’s National ID Debate Sparks New Political Fault Line

GAROWE, Somalia — A political storm is gathering around Somalia’s fragile national identification rollout, after Puntland’s information minister delivered an unusually fierce rebuke of President Hassan Sheikh Mohamud’s suggestion that al-Shabab members could obtain the country’s new NIRA identity card.

The remarks, delivered at a tense press conference in Garowe, laid bare the widening rift between the federal government and the country's oldest Federal State over security strategy, citizenship, and control of national institutions.

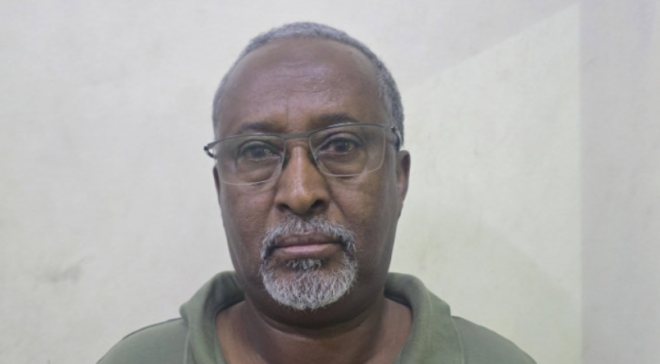

Mohamud Aydid Dirir, Puntland’s information minister, did not mince words. Standing before a row of local reporters, he condemned the president’s position as reckless and dangerous. “Anyone who takes the NIRA card will be considered hostile, and we will arrest them,” he declared. For Dirir, the issue is not merely procedural — it is existential.

He argued that the identity card program “was originally introduced illegally,” claiming it lacked national consensus from the start. “Hassan is the president now, and he is the one saying he will give IDs to al-Shabab,” he added, framing the policy as both misguided and politically isolating.

Behind Dirir’s sharp tone lies a deeper suspicion: that the federal government is not fully committed to the war against al-Shabab. He accused Mogadishu of maintaining “working relations” with the militant group, arguing that such ties undermine the sacrifices made by security forces and local communities battling the insurgency.

The controversy erupted after President Hassan Sheikh, speaking at the close of the National ID conference in Mogadishu, said al-Shabab members — who are Somali citizens — could technically receive the new cards. He insisted the government was aware the group would likely send intermediaries to register, but argued that documenting their fingerprints and faces would ultimately strengthen security.

“If they take the card, we will have their data,” the president said, portraying the system as a tool for long-term counterterrorism tracking.

But in Puntland, where the regional government has fought its own fierce battles against militants in the mountains of Bari and Sanaag, the proposal has landed with a thud. Officials there fear the card could offer militants a veneer of legitimacy — or worse, mobility.

The clash underscores the fraught nature of Somalia’s state-building process: even a seemingly administrative step like a national ID can quickly spiral into a struggle over power, trust, and the meaning of citizenship in a country still navigating conflict and political fragmentation.

As both sides harden their positions, the debate over NIRA cards has morphed into something larger — a test of Somalia’s ability to craft unified national policies in a landscape where security and politics remain inseparable.

GAROWE ONLINE